BY |

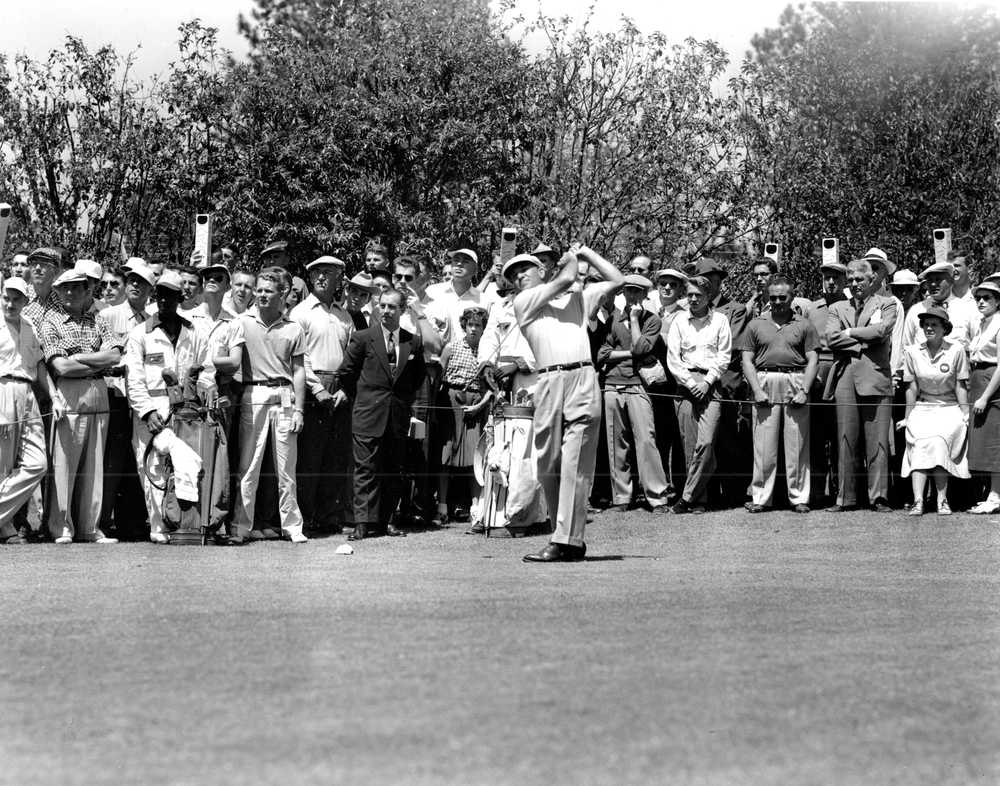

Year of failures led up to Ben Hogan's Triple Crown in 1953

To understand the origins of Ben Hogan’s magnificent 1953 campaign, you have to understand the failures he experienced in 1952.

At the Masters Tournament, Hogan was tied with Sam Snead for the 54-hole lead but tumbled to 79 in the final round.

“Worst round he’d ever shot,” veteran golf writer Dan Jenkins said. “He didn’t play bad, it was just windy and he didn’t get any breaks.”

At the U.S. Open, Hogan held the 36-hole lead but came unglued early in the 36-hole finale. He finished with a pair of 74s.

“He lost it on the sixth hole of the morning round,” Jenkins said. “Hit a great shot. Overpured it. Made double bogey.”

Hogan’s only win in 1952 came at the Colonial National Invitation in his hometown of Fort Worth, Texas. Because of his near-fatal car crash in 1949, Hogan played a limited schedule. He no longer competed in the PGA Championship, which had a grueling match-play format, and he had never played in the British Open.

Hogan turned 40 in August 1952, and he knew his opportunities were running out. He vowed to make 1953 count.

“He was driven to get even,” said Jenkins, who covered Hogan’s exploits for the Fort Worth Press. “It was part of his makeup.”

Hogan did just that. He played in an unofficial event in January in Palm Springs, Calif., finishing two shots behind winner Jimmy Demaret.

Hogan didn’t play in any official events and arrived early to practice in Augusta. Sportswriter Randy Russell of The Augusta Chronicle made a prophetic statement in his column on the Sunday before the Masters.

“He has spent two weeks tuning up for the Masters,” Russell wrote. “Watch out for him.”

By the time the tournament started, however, the media were talking about another Texan. Lloyd Mangrum shot 9-under 63 in Wednesday’s practice round. The score was one shot better than the official course record he set in the opening round of 1940.

Chick Harbert shot 4-under 68 to take the lead on the first day, and Hogan was close behind with 70. Hogan took the lead on the second day when his 69 put him ahead by one shot.

Every tournament his its defining round or moment, and Hogan’s came in the third round. He blitzed Augusta National with his best round there – 6-under 66 – to open up a four-shot lead. Hogan made birdies at Nos. 2, 4, 8 and 9 to make the turn in 32, and he added birdies at Nos. 10, 14 and 15. The only blemish on his card was a bogey at No. 16, where he 3-putted from 30 feet.

With a 54-hole total of 205, Hogan was in uncharted Masters territory. He could shoot over par in the final round and still break the tournament’s 72-hole scoring record.

Shooting over par, like he did in the final rounds of the Masters and U.S. Open a year earlier, was not Hogan’s style. Playing alongside friend and rival Byron Nelson, who was customarily paired with the leader, Hogan polished off the tournament with 69. The 14-under par total of 274 shattered the previous record of 279.

“He said at the time it was the greatest golf he’d ever played for 72 holes,” Jenkins said. “And it was.”

Hogan, who carded five birdies against two bogeys in the final round, agreed.

“I hit the ball better – more like I wanted to hit it – than in any 72-hole tournament I’ve ever played,” Hogan said after the final round. “Before the tournament started I knew I was playing the best golf of my life, and I knew that if I played in the tourney the way I did while practicing I would win. At least I was going to give a real college try.”

Hogan’s season of excellence was just beginning. Two weeks later, he won the Pan American Open in Mexico City, and he followed that by defending his title with a five-shot victory at Colonial.

His only blemish, if you could call it that, came in between those wins at the unofficial Greenbrier Pro-Am. He tied for third, four shots behind Snead.

Up next for Hogan was the U.S. Open, which was being held at Oakmont.

The rugged course outside Pittsburgh was no match for Hogan, who started with rounds of 67 and 72. But hot on his heels was Snead, and after Hogan stumbled to 73 in the third round, Snead trailed only by one.

Hogan wouldn’t stumble like he did a year earlier. Playing ahead of Snead, Hogan played steady golf. He would frequently ask others, including Jenkins, how Snead was faring.

“Sam was doing alright at the time, but (Hogan) finished 3-3-3,” Jenkins said.

Snead finished with 76 to Hogan’s 71, and the Texan had picked off another major.

“He just killed everyone,” Jenkins said. “He killed Snead at Oakmont.”

Hogan had said at the Masters that he wouldn’t travel overseas for the British Open, but he had a change of heart. The championship was played at Carnoustie, and Hogan went to Scotland a few weeks early to get used to the conditions.

“It’s true that when he went to a major to a course he had never played before, he’d walk it backwards first to see what all he wanted to avoid,” Jenkins said. “He just studied it like a scientist. That was his temperament. He was so meticulous in everything he did.”

The extra work paid off as Hogan recorded a four-stroke victory with rounds of 73, 71, 70 and 68. He entered the final round tied with Roberto De Vicenzo, but an early string of birdies gave Hogan the edge he needed.

Though the Scots adored Hogan, he wasn’t too keen on the course. It was his first, and last, appearance at the British Open.

“I’ve got a lawn mower back in Texas, I’ll send it over,” Hogan famously said after winning.

The PGA Championship and British Open dates overlapped that year, so winning all four majors was impossible. But Hogan had done something just as special as Bobby Jones did in his Grand Slam season of 1930, and the press dubbed it the “Hogan Slam” or “Hogan’s Triple Crown.”

He recorded five wins in six starts, and three of those came in majors.

After returning to New York from Scotland, the “Wee Ice Mon” was greeted with a ticker-tape parade. It was the first time a golfer had been so honored since Jones in 1930.

1963

Arnold Palmer was the undisputed king of golf, and the Masters, from the late 1950s through the early 1960s. But trouble was brewing for Arnie’s Army in the form of Jack William Nicklaus.

The pudgy amateur had turned pro in 1962 and promptly unseated the king at that year’s U.S. Open in Palmer’s home state of Pennsylvania.

Neither Palmer nor Nicklaus got off to a good start at the 1963 Masters. Both opened with 74s that left them five shots off the pace.

Nicklaus recovered in the second round with 66, the best score of the tournament, and trailed Mike Souchak by one at the midway point. Nicklaus posted 74 in the third round, but with Augusta National playing difficult on a rainy day, it was enough to put him into the lead.

Palmer was not in the running – he followed his opening round with scores of 73, 73 and 71 – but Tony Lema, Sam Snead and Julius Boros all made moves in the final round as Nicklaus struggled. Through 12 holes, he was 2-over par for the day.

He responded by making birdies at the 13th and the 16th, the latter on a delicate 12-foot putt. Two pars later, Nicklaus had completed his 72 and held off Lema by one stroke. His victory, at age 23, made him the youngest Masters winner at the time.

Alfred Wright, writing in Sports Illustrated, commented on the size of Nicklaus’ coat and what the future held for the young golfer.

“The size is 44 regular, and they may as well file it where it will be handy,” Wright wrote. “Jack may earn a few more of those coats in the future.”

1973

Growing up in Gainesville, Ga., Tommy Aaron often dreamed of playing in the Masters. Amateur legend Bobby Jones, a Georgia native, had started Augusta National and the Masters after his playing career was over.

Claude Harmon had become the first native Georgian to win the Masters in 1948, but the state had not produced any other Masters champions since.

Aaron changed that in 1973. A 68 in the first round gave him the outright lead, and he backed it up with 73 to enter a four-way tie for first. Saturday’s third round was washed out by rain, which meant the golfers would have to finish on Monday.

Aaron struggled to 74 in the third round, and Englishman Peter Oosterhuis seized the lead with a fine 68.

Aaron trailed Oosterhuis by four shots going into the final round, but he finished with 68 to nip J.C. Snead by a stroke and claim his only major victory.

Aaron had been involved in the Roberto De Vicenzo scorecard incident in 1968 when he marked down an incorrect score for his playing partner. De Vicenzo signed the incorrect scorecard and was forced to take the higher score, which left him one shot behind winner Bob Goalby.

Ironically, Aaron caught a mistake on his scorecard at the 1973 Masters. Playing partner Johnny Miller had marked down a 5 on No. 13 for Aaron, but he had made birdie 4.

“Winning the Masters for me was a dream come true,” Aaron wrote in 2012. “From the time I started playing in Gainesville, Ga., northeast of Atlanta, I thought the Masters was the only golf tournament in the world.”

1983

Seve Ballesteros always had a flair for the dramatic.

Whether it was winning the British Open despite errant tee shots or becoming the youngest Masters champion with some final nine adventures, the Spaniard was anything but dull.

Ballesteros got off to a fast start in search of his second green jacket in 1983. His opening round of 68 put him squarely in the mix.

Rain on Friday washed out the second round and pushed the tournament a day behind schedule. Still, Ballesteros posted scores of 70 and 73 on the weekend and entered Monday’s final round one shot behind co-leaders Craig Stadler and Raymond Floyd.

Ballesteros could not have dreamed of a better start to the final round. He began with a birdie on the first hole, added an eagle on the par-5 second and claimed another birdie at the fourth. He was 4-under for four holes and in control, but Ballesteros rarely won without some drama.

He maintained a comfortable lead until Amen Corner, where he made bogey on the 12th hole. After he snap-hooked his drive into the woods on No. 13, he was able to salvage par by pitching out and reaching the green in regulation.

“I told my caddie after I parred 13 that ‘from here to the last hole we have to play the last holes in par,’ and we did,” Ballesteros said.

That included a chip-in for par on the final hole, though the tournament had been decided by that point. Ballesteros won by four shots over Tom Kite and Ben Crenshaw.

Once again, the Spaniard’s style left everyone shaking their heads.

“It was like he was driving a Ferrari and everybody else was in Chevrolets,” Kite said.

1993

Make no mistake: Bernhard Langer won the Masters twice thanks to terrific play and gutsy decisions.

Both of the German’s victories - 1985 and 1993 - also will be remembered for back-nine decisions by players who wound up losers.

In the final round in 1985, Curtis Strange found the water at Nos. 13 and 15 and made bogeys while Langer shot 68 to win his first major.

Eight years after his first triumph at Augusta National, Langer used another back-nine charge on Sunday to earn a green coat.

Holding a slim lead over Dan Forsman and Chip Beck, Langer made pars on Nos. 11 and 12 and an eagle on the par-5 13th to pull away.

Forsman made a quadruple bogey on the par-3 12th to fall out of contention.

Langer was paired with Beck, a former University of Georgia golfer. On the par-5 15th, facing a three-shot deficit, Beck elected to lay up instead of going for the green in two from 236 yards away. He wound up making par while Langer birdied to push the lead to four and wrap up the victory.

“I was a little surprised he laid up,” Langer said. “My caddie said, ‘He’s got to go for it if he wants to have any chance to win.’ I said, ‘I agree.’”

2003

Conventional wisdom holds that the Masters is usually won by long hitters. Being a right-hander with the ability to hit a powerful draw is usually a plus.

But a year after Augusta National underwent its most extensive renovations, southpaw Mike Weir turned that thinking on its head.

The tournament started with all eyes on Tiger Woods as he went for an unprecedented third Masters win in a row. But three rounds over par put those ambitions at bay.

Instead, the tournament produced a battle between journeymen Weir, Len Mattiace and Jeff Maggert.

Mattiace closed with 65 in the final round and held the clubhouse lead despite a bogey on the final hole.

Weir, a Canadian who was beginning to emerge as a rising star, caught Mattiace with clutch birdies on the final nine. Then, he saved par with a clutch 7-footer on the final hole to set up a sudden-death playoff with Mattiace.

The odds seemed to favor Mattiace, who had the hot hand, and not the short-hitting Canadian who played from the “wrong” side.

But on the playoff’s first hole, the 10th, Mattiace pulled his approach left of the green. His chip ended up 30 feet away, and his par putt didn’t come close. When he missed his bogey putt, Weir tapped in for bogey to collect a green jacket.

He became the first left-handed golfer to win the Masters and the first Canadian to win a major.

Another reward for Weir was a phone call from Jean Chretien, Canada’s prime minister.

“He said they were jumping up and down,” Weir said. “They were very excited.”

ONE OF SIX

Jack Nicklaus is the only golfer with six Masters victories. His win in 1963 at age 23 made him the youngest champion at the time. He later became the oldest champion with his win at age 46 in 1986.

Abraham Ancer

Abraham Ancer

Daniel Berger

Daniel Berger

Christiaan Bezuidenhout

Christiaan Bezuidenhout

Patrick Cantlay

Patrick Cantlay

Paul Casey

Paul Casey

Cameron Champ

Cameron Champ

Stewart Cink

Stewart Cink

Corey Conners

Corey Conners

Fred Couples

Fred Couples

Jason Day

Jason Day

Bryson DeChambeau

Bryson DeChambeau

Harris English

Harris English

Tony Finau

Tony Finau

Matthew Fitzpatrick

Matthew Fitzpatrick

Tommy Fleetwood

Tommy Fleetwood

Dylan Frittelli

Dylan Frittelli

Sergio Garcia

Sergio Garcia

Brian Gay

Brian Gay

Lanto Griffin

Lanto Griffin

Brian Harman

Brian Harman

Tyrrell Hatton

Tyrrell Hatton

Jim Herman

Jim Herman

Max Homa

Max Homa

Billy Horschel

Billy Horschel

Viktor Hovland

Viktor Hovland

Mackenzie Hughes

Mackenzie Hughes

Sungjae Im

Sungjae Im

Zach Johnson

Zach Johnson

Dustin Johnson

Dustin Johnson

Matt Jones

Matt Jones

Si Woo Kim

Si Woo Kim

Kevin Kisner

Kevin Kisner

Brooks Koepka

Brooks Koepka

Jason Kokrak

Jason Kokrak

Matt Kuchar

Matt Kuchar

Martin Laird

Martin Laird

Bernhard Langer

Bernhard Langer

Marc Leishman

Marc Leishman

Joe Long

Joe Long

Shane Lowry

Shane Lowry

Sandy Lyle

Sandy Lyle

Robert MacIntyre

Robert MacIntyre

Hideki Matsuyama

Hideki Matsuyama

Rory McIlroy

Rory McIlroy

Phil Mickelson

Phil Mickelson

Larry Mize

Larry Mize

Francesco Molinari

Francesco Molinari

Collin Morikawa

Collin Morikawa

Sebastian Munoz

Sebastian Munoz

Kevin Na

Kevin Na

Joaquin Niemann

Joaquin Niemann

Jose Maria Olazabal

Jose Maria Olazabal

Louis Oosthuizen

Louis Oosthuizen

Carlos Ortiz

Carlos Ortiz

Charles Osborne

Charles Osborne

Ryan Palmer

Ryan Palmer

C.T. Pan

C.T. Pan

Victor Perez

Victor Perez

Ian Poulter

Ian Poulter

Jon Rahm

Jon Rahm

Patrick Reed

Patrick Reed

Justin Rose

Justin Rose

Xander Schauffele

Xander Schauffele

Scottie Scheffler

Scottie Scheffler

Charl Schwartzel

Charl Schwartzel

Adam Scott

Adam Scott

Webb Simpson

Webb Simpson

Vijay Singh

Vijay Singh

Cameron Smith

Cameron Smith

Jordan Spieth

Jordan Spieth

Henrik Stenson

Henrik Stenson

Tyler Strafaci

Tyler Strafaci

Robert Streb

Robert Streb

Hudson Swafford

Hudson Swafford

Justin Thomas

Justin Thomas

Michael Thompson

Michael Thompson

Brendon Todd

Brendon Todd

Jimmy Walker

Jimmy Walker

Matt Wallace

Matt Wallace

Bubba Watson

Bubba Watson

Mike Weir

Mike Weir

Lee Westwood

Lee Westwood

Bernd Wiesberger

Bernd Wiesberger

Danny Willett

Danny Willett

Matthew Wolff

Matthew Wolff

Gary Woodland

Gary Woodland

Ian Woosnam

Ian Woosnam

Will Zalatoris

Will Zalatoris